As Is: Pop and Complicity

Left: As Is dialog. Right: (L-R) Ginger Wolfe-Suarez, Glen Helfand and Patricia Maloney.

As Is dialog.

Transcript of an open dialog

June 12, 2010

Sight School, Oakland, CA

What’s the role of pleasure in art?

How do you gauge sincerity?

Can Pop art transcend radical negative consumerist critique?

Who adds value to discount materials—artist

or viewer?

Is positive psychology science or superstition?

In conjunction with Irrational Exuberance (Asst. Colors), Sight School and Christine Wong Yap organized As Is: Pop & Complicity, an open dialog featuring critic and curator Glen Helfand (Artforum, Salon, Wired, San Francisco Bay Guardian) and artist, writer and theorist Ginger Wolfe-Suarez (Co-Founder & Editor, interreview.org; represented locally by Silverman Gallery). It was moderated by curator and writer Patricia Maloney (Editor-in-Chief, Art Practical; Artforum, Bad at Sports). The transcript below was edited for brevity.

Patricia Maloney: Do you think of yourself as an optimist

or a pessimist?

Glen Helfand: I’m ambivalent. I like to think of myself as an optimist, but I don’t know if I really am.

Ginger Wolfe-Suarez: I guess I’m an optimist; I hope I have the ability to do both.

PM: Do you think that there are particular circumstances that warrant pessimism or optimism?

GH: Look at the world right now—the oil spill in the Gulf. It seems completely horrifying. And yet, life goes on, which is in a sense, optimism; that we continue to survive in some way.

GWS: I think going beyond this arbitrary boundary between optimism and pessimism and having the ability to think critically is really important.

GH: Considering some of the conversations we’ve had recently, criticality tends to be viewed as pessimistic.

Cai Guo-Qiang, Fireworks from Heaven, 2001, mixed media, dimensions

variable, detail of installation view, Yokohama Triennale. Photo:

Masatoshi Tatsumi. Source: BAM/PFA.

Christian Marclay, Video Quartet, 2002. Source: Tate.org.uk.

Pipilotti Rist, Pepperminta, 2009, film still. Courtesy of the Artist. Source: Art Practical.

PM: The title of this exhibition, Irrational Exuberance, suggests that viewing a work of art might convey pleasure. Is it OK for art to be pleasurable?

GH: Totally! I think it should be. I’m so excited when something really is pleasurable. The fireworks guy—

Audience member: Cai Guo-Qiang.

GH: —did a piece at the Berkeley Art Museum with massage chairs and flashing lights. That was the most purely pleasurable exhibition. I was just so happy. Christian Marclay’s Video Quartet is just a purely pleasurable musical-visual treat. It really makes me feel like I believe in art.

GWS: The simple answer would be: Why wouldn’t it be OK for art to be pleasurable? I think a lot of gauntlets have been laid in contemporary art criticism and contemporary art history about the role of pleasure.

PM: Where does that pleasure in art come from? What does it mean for a work of art to trigger a sincere response from the viewer?

Audience member: The pleasure in Cai Guo-Quiang’s piece is that it’s smart. Those two experiences, simultaneously relaxing and jolting—

GH: Right! It’s about the sweet, and… salt, the leveling element—

Audience member: There’s some kind of dynamic there.

GH: I wrote an article about the Pipilotti Rist film for Art Practical. She is another artist who deals with pleasure. Her work is always so goofy and colorful, and yet, there’s always this weirdness and allusions to political scenarios—

Audience member: Well, violence.

GH: —violence, yes, but it’s treated in a way that’s so original. The result is exuberance. I felt great after I saw that film.

Alfredo Jaar, Public Presentation of Happy and Unhappy People, 1980. Source: AlfredoJaar.net.

GWS: Pleasure can be a rejectionist term; one has to be careful. Alfredo Jaar is someone I think about a great deal; he’s a phenomenal artist. He’s widely known for his work on genocide in Africa, and less known for Studies on Happiness[1] in South America in the 1970s. Alfredo’s practice is about generosity and transformation, and not all of it has to do with pleasure.

GH: But even his work on genocide—it’s satisfying the way he’s been able to deal with that subject.

GWS: He’s able to transform it into a collective experience.

PM: Tell me more about generosity in his practice. It implies a gift, a share of resources offered.

GWS: His work is about something more than sharing; it’s about discovery. It’s about re-articulating human-ness and human experience in a way that was profound to me.

Andy Warhol, selection from Time Capsule 21: Greeting card: "Inky

brings a warm 'Hello!'"), n.d., handwritten, ink on printed cardstock

with velvet details, 6 15/16 x 5 3/11 in. Source: Warhol

Museum Time

Capsule 21 site.

Andreas Gursky, 99 Cent, 1999, chromogenic color print,

6' 9 1/2" x 11' (207 x 337 cm).

Lent by the artist, courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, New York,

and Monika Sprüth Galerie, Cologne.

©2001 Andreas Gursky. Source: MOMA.org.

99¢ Only

stores website, with Gursky's photo

PM: Generosity suggests reception; Christine’s work exhibits a consciousness of experience, of what we are receiving. In her interview with Steven Barich on Artopic, Christine said, “Psychological experiments have shown that experiences matter more than things.” What happens when that experience originates from things?

GH: I’m reading a book about hoarding, which I find fascinating; that kind of darkness in light. People start off getting a lot of pleasure from acquiring objects—I'm sure there are plenty of collectors who might be hoarders of art.… And Warhol’s time capsules, apparently, were a hoarding act.

GWS: I think there is a real boundary between visual pleasure in classical art criticism and pleasure as it butts against idea of happiness. I think those are two different concepts. I’m really interested in the part about happiness because the Kantian ideas of pleasure are outdated.

PM: Those ideas of visual pleasure also reinforce taste. In this space, there’s a refutation of that sense of visual pleasure for a sense of pleasure as happiness by adopting the aesthetic of the discount store. There is a lot offered in terms of what it means to acquire pleasure.

GH: Or that our cultural imperative is that we all should get pleasure. What about the idea that we can’t always have that? The discount store is a weird example—We can have it all, but it’s gonna break tomorrow. So is it really happiness?

Artist and curator Joseph Del Pesco: The toys in the 99¢ store near my house have mercury in them. Even worse than that, they have been tracking who shops at the 99¢ stores by credit card, and it ticks against their credit rating. They identify poor people by who shops in the 99¢ store.

GH: I think it’s interesting that many artists frequent them for art supplies! Watch out!

PM: Pay in cash!

JDP: There’s a sinister underbelly underneath, under this sheen of—

GH: Accessibility. Right! Which is why I still love seeing the Andreas Gursky photo [of a discount store], it’s just so glittering and amazing and colorful—

JDP: Which incidentally, the same 99¢ store uses on their website to promote their store.

GH: But apparently that photograph is fading.

Audience members: The inks they used are not archival.

GH: I wish I believed that he did that on purpose.

Haim Steinbach, Six Feet Under, 2004

plastic laminated wood shelf; plasitc frog; plastic feet; ceramic

pig; wooden clogs

38 x 69 1/4 x 19 “ (96.5 x 175.9 x 48.3 cm). Source: HaimSteinbach.net.

Allan McCollum, Surrogate Paintings, 1978-79, acrylics and

enamels on wood and museum board. Installation: 112 Workshop, New York

City, 1979. Source: AllanMcCollum.net.

GWS: The aesthetics of Christine’s work has to do with consumption—another word that’s been used as a rejectionist term. I’m interested in looking at Christine’s work, and work like Christine’s, that transcends consumption as a closed system of signs and symbols. That conversation can be transformative. I’m interested in that potentiality because I don’t think it’s happened. I worked a little bit with Haim Steinbach and I had some communication with Allan McCollum early on, and I was really interested in how they talked about their objects. I think the academic conversation happening by people like Foster did people like Haim Steinbach a disservice. That disservice didn’t happen in Europe. It happened here. There are political ramifications for words like consumption—like nihilation—so I think the ability to tackle, and transcend, those conversations is really exciting for me. I think that can happen around this show.

GH: How did Steinbach talk about consumption?

GWS: He makes one important differentiation between his work and Allan McCollum’s work, and that is that he uses real objects. His objects aren’t about repetition. His objects are about creating relationships amongst people and amongst objects, and transcending this question about consumption, which was embraced in Koons’ and McCollum’s work. I’ve been going back and reading through post-Jamesonian ideas about capitalism. Now in 2010, we can revisit that in a more productive way.

Jeff

Koons, Inflatable Flower and Bunny (Tall White, Pink

Bunny), vinyl, mirrors

32 x 25 x 18 inches,

81.3 x 63.5 x 45.7 cm. Source: JeffKoons.com.

Libby Black, Back in the Saddle Again, 2007, paper, hot glue,

acrylic paint, 35 x 15 x 30 inches. Source: LibbyBlack.com.

Stephanie Syjuco, notMOMA, 2010. installation view, handmade illicit

artworks by the artist and university art students. Source: StephanieSyjuco.com.

Takashi Murakami at MOCA. Photo: Glenn Koenig / Los Angeles Times. Source: LATimes.com.

PM: Christine also speaks about how her work might create relationships between viewers. She says, “Viewers need not buy or own a thing to engage an experience.”

GH: I think it’s interesting to consider craft here, and the recent work of Libby Black and Stephanie Syjuco. Now, we’re in an economic downturn. Christine mentioned Murakami’s Louis Vuitton store in correspondence. I thought that was an amazing piece at that moment. To encounter that piece now would completely not work because of the luxury status. And yet wanting objects, creating an allure of objects, is more complicated. It seems to be in making stuff on Etsy distribution networks, of things that are humble but still sort of expensive, like artisanal food….

JDP: Even the labor of knitting or crocheting—you can buy that scarf for $10 at the Gap, but to actually produce it, your labor hours would cost $200. That’s hidden inside of ‘craft.’

Audience member: The big thing missing in Kant is class consciousness…. If something reminds me of a dollar store, my response depends on what my class is…. I might be like, Wow, this is great, I want everything in it, and I can afford it because I’m poor, or maybe I’m pretentious and middle-class, and I’m like, That’s disgusting, that’s cheap crap that poor people buy, or maybe I’m a hyper-educated artist that thinks That’s cool, because that’s where I get my supplies. So there’s pleasure and displeasure but it’s all based on my class background—or my education.

GWS: There’s this underlying idea that things in dollar stores are super accessible, and the reality is that they’re not accessible to everyone. It’s also about production.

Artist and critic Peter Dobey: Dollar stores are where poor people can buy things produced by even poorer people in near slave labor conditions.

GH: Here are things about this shimmering surface, yet, is that sort of visual pleasure a necessity? The shimmering object versus daily staples: the need to buy food versus the gorgeous pink cookies in the other room.

GWS: When all these articles came out in the 1970s and 1980s on Steinbach’s work, they were talking about consumption as a closed system of signs. Within that was an embedded refusal to talk about objecthood and what the objects meant.

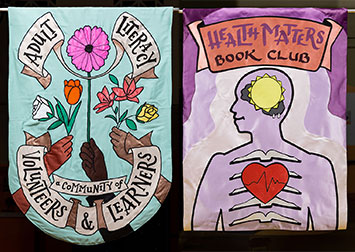

Christine Wong Yap, Banner #1, 2010.

PM: This brings up how experiences are not just phenomenological, but metaphorical. They function in a way that our recognition of the gesture embeds meaning and understanding. So you can have a completely non-linguistic experience that is highly metaphorical.

GH: The term that comes to mind is ‘added value.' I’m attracted to these Banner photographs. Learning what they’re made of makes them more exciting to me. They’re these cheesy gift bags that have been transformed. Even though they’re working in the language that the materials are intended to be about, like the notion of the gift, they now become something ghostly. There’s an added layer of what the artist can bring to the materials.

Artist and blogger Steven Barich: What is the experiment that is going on here that the artist has presented to us as viewers? We could look at it cynically about how we approach art. Maybe it’s showing our desire to like something that actually isn’t likeable. It’s an object, but it’s meant to reflect back to us our opinions about how we come into a gallery space and look at something to consume or understand it, and how we’ll never be able to do that if the artist is showing us ourselves, more than asking us to appreciate the work in front of us.

JDP: There’s a cheap, trashy material language. When you say ‘added value,’ I think of taking these things that cost less than a dollar, and doing something to them, or giving them a kind of value through turning them into a crafted object. That is adding value to an object. It’s beyond just presenting us with materials like Haim Steinbach is doing, which is putting things on a shelf as an act of appropriation and dealing with these objects in the context of the art world or art frame. I think there is added value here.

GH: I’m intrigued by the term ‘likeability.’ That something is un-likeable and yet, don’t they still need to seduce us, in a certain way?

SB: But it could seduce us on a purely conceptual level. Once you understand the idea, is that the seduction? The artist’s challenge is to find that avenue to seduce us, and then one can judge the show on these avenues? Isn’t this interaction of seduction between the artwork and viewer part of the pleasure?

Curator and writer Julia Hamilton: I’m curious about what the value is of the ‘added value’…. It’s hard for me to look at art that deals with materiality as a subject, and not feel that it isn’t returned to the shelf, as a higher form of commodity.

PD: That’s actually my question: how much of it is critiquing consumerism and how much of it, on a root level, is reinterpreting—

JDP: Or kind of capitulating?

PD: —consumerism and desire.

JDP: Well, we should think about where we are, too.

PD: Right.

JDP: We’re not in Chelsea, for example. [To Michelle Blade] No offense.

[Laughter.]

Artist Christine Wong Yap: I think about the objects in a store or in a domestic setting, about how people of all classes have knick-knacks, about that fine line between how something might be a decorative plate, but to someone, it’s also their art.

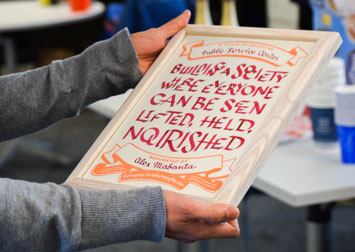

Give a Can, Take a Can in Super Pop-Up Shop at Alameda Towne Center, Alameda, CA, November 2009.

GH: Retail is viewed as so much more democratic than the art venue. The language of these things is so ingrained in us. I did a project last fall—the Super Pop-up Shop. It was a class at the California College of the Arts where people have to create projects for a mall in Alameda. What was so satisfying about that project was talking to people in this environment that was not an art environment—the dialogue involved with retail transactions. We became shopkeepers. We had to lure the public—seduce people—and explain ourselves to them: we want to give you an experience; we want your approval, in a certain way. It’s interesting to me how you subvert this language….

PM: In the conversation thus far, there’s been an assumption of critique within the exhibition. Is that, in fact, what’s happening? Perhaps, rather, it’s an embrace of this aesthetic.

Artist Justin Limoges: Some of Christine’s intention is to foster a dialogue about of optimism and pessimism. It’s interesting that in the way this conversation has been going, there’s more emphasis placed on whether it is sincere or cynical in its underlying imperative. I think that’s a logic of people with critical perspectives or art historical backgrounds, but it’s interesting how people blanch at optimism/pessimism as a flat question. There is real sincerity in this work; that’s borne out of appreciation of the materials. A lot of people go to a dollar store and appreciate what’s there. There is validity in having a direct relationship with a 99¢ object that could eventually become talismanic, that people really live with and love.

GWS: The cynicism of the dollar store, and shopping there, may be unfounded in some circumstances. I hope this show transcends that, and that people have a conversation that goes beyond a closed system of signs, because I think that needs to happen…. Someone should write about it in the history of the art object, in a way that acknowledges the historical precedents for this work.

Amanda Ross-Ho, Installation view of The Cheshire

Cat Principle, Pomona College Museum of Art. Source: CherryandMartin.com.

Claes Oldenburg, The Store, 1961. Photo: Robert R. McElroy.

Source: Artnet.com.

Cary Leibowitz, a re-creation of Leibowitz’ iconic

Candy Ass Carnival installations from the early 1990s. Art Forum Berlin,

2007. Source: Alexander

Gray Associates.

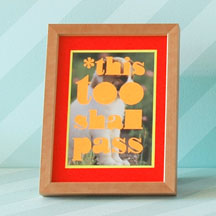

Christine Wong Yap, This Too Shall Pass, 2010.

PM: Can we talk about the precedents for this work? There’s the history of the installation as store, and the genealogy of Pop art.

JDP: One might even ask: Is there too much precedent for this work? Does it feel like a bit of Koons and Steinbach?

GWS: Or Amanda Ross-Ho, who also deals with trying to transcend consumption and re-articulating the act of making things.

PM: And Christine’s contemporaries embracing the same questions, like Stephanie Syjuco. Where the craft is inherent, but there’s a similar ambivalent embrace.

GH: And Libby Black as well. I think the interesting thing is how the individual plugs into that framework of the retail establishment; Oldenburg was the guy sitting in that store; Cary Leibowitz creating works like self-portraits out of really cheap objects and distributing them by making them available to people. So to me that’s what’s interesting—how an artist sells themselves within these things because it’s such a psychological experience. And even in the way this body of work is looking at motivational optimism and pessimism, and how we keep going. These This Too Shall Pass collages; the ambivalence about them. What is the cutesy imagery that’s gonna go away? What’s gonna come after? A good thing or bad thing? Something more tasteful?

PM: I keep coming back to taste and sincerity. Is it possible to be sincere around this aesthetic? Is it possible, in light of Christine’s other work, to approach this and recognize it as sincere within the artist’s own objectives? To what extent is she offering her own definition of pleasure and happiness?

GH: Or does the act of making artwork generate happiness for the artist?

GWS: I think it’s ethical too. The idea that happiness means the same thing to all of us is a big issue in common ethics and philosophy right now. It’s a complicated question—one that we’d all answer differently.

Writer Victoria Gannon: My impression of the show is that it’s a sincere embrace of different things that are supposed to make you happy, like an experiment. Christine has mentioned the embrace of optimism as a choice. Here, she’s taken a lot of objects that supposedly exude a lot of optimism to see what sort of effect they may have. I don’t think the sentiment in the objects is sincere, but the sentiment in her embrace of that possibility is.

DB: You could be a very sincere consumer.

GH: That experiment idea suggests a therapeutic quality. Someone earlier was saying how good this color looks in here, and what it does psychologically, like the fast food interior colors that are supposed to make you hungry. What does it really do physiologically?

PM: Positive psychology purports that things which we consider irrational or emotional are actually things that we can identify and embrace in a very systematic way; that there are behavior modification processes by which we can acquire optimism and happiness. I’m curious about the ways that a psychological process parallels a critical process. Back to Cao Guo-Quiang, and the pure sensory pleasure alongside the critical consideration, I feel that what’s colliding here in this exhibition are the psychological and critical processes.

JDP: When you use this aphoristic language, like happiness and pleasure, it sounds like joining a cult to me. I’m not saying those terms are totally emptied out. The way people like Stephanie Syjuco direct an exchange and interaction with the same material seems to be clear as to what she’s saying. This seems more open. If that’s Christine’s approach—positive, or positivist, psychology—that’s fine, but that’s not necessarily important to us as viewers. We’re allowed to have our own reading in this polyvalent, pluralistic world of art. Not to say that we should discount it, but I’m not reading this kind of material from this work. I’m not reading happiness. It seems complex, sad and dark to me.

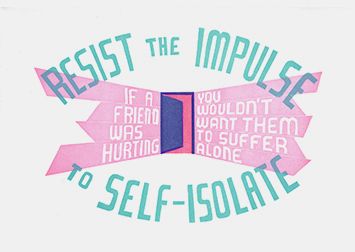

Audience member: There are a lot of dark undertones. I love that little banner that reads I Like Myself.

JDP: As if that would do it, right?

PD: Positive psychology sort of functions on that your irrationalities are just that—irrational, and therefore unproductive. Coming from a psychoanalytic perspective, the idea of changing your behavior is completely problematic. It’s changing it towards what? To be inside the realm of normality?

Christine Wong Yap, Vinyl

Ficus #3 & 4, 2010, vinyl, mylar,

thread, lacing, wire, ~18 x 12 x 12 inches / 45 x 30 x30 cm each.

Christine Wong Yap, The

Best Person I Can Be (exterior view), 2008, installation:

security mirrors, frame, lights, fixtures, wall, 8 x 8 x 8 feet / 2.4 x 2.4

x 2.4 m. photo: Bob Hsiang.

Christine Wong Yap, Cycle of Optimism / Pessimism.

Urs Fischer, Service à la française, 2009, silkscreen on mirrored chrome steel, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist; Gavin Brown's enterprise, New York; Sadie Coles HQ, London; and Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zürich. Installation view: “Urs Fischer: Marguerite de Ponty.” Photograph by Benoit Pailley. Source: NewMuseum.org.

GH: We haven’t talked so much about thinness. Everything’s veneer. It’s about putting gold spray paint, or silver mylar, over something that’s more complicated. Remember the skeletal gift boxes Christine did? They were skeletons that contained nothing, in a way, like the skeletons of Vinyl Ficus. So, what is in the notion of just applying something to that surface?

JH: To me, these objects are very familiar… It’s interesting to me because it conjures up memories. I think there’s something populist about these things; it helps connect me to people around me, to my family, to people who purchase these things. I think there’s something very sincere and hopeful—not optimistic—there’s a hope in the fact that there’s familiarity in terms of these objects. There’s something to be said about objects that connect you to the people around you in a different way.

Artist Amanda Curreri: This is sort of a next step for Christine’s work with mirrors. You’re making a space—a room without mirrors—but it’s a mirror for us, as a public. This is a mirror for a lot of language at one time. We all own it, but it’s us. It seems like a neat jump to be able to make a reflection of us without a physical mirror.

PM: What is the extent to which we are reading this work versus experiencing it?

Michelle Blade, Artist and Sight School Director: This ties into the first question, whether they are optimists or not. I think this is what the show is asking all of us to do. And I completely agree with what Joseph was saying, and I do see a dark undertone. But it’s a person coming to this kind of cultural language from an honest position, where she’s trying to see the positive side….

VG: Christine’s other work presented optimism and pessimism as a spectrum: once you get to the extremes of optimism, you’d fall through to pessimism. I see that here too. You wouldn’t get to the point where you were embracing positive psychology unless things were bleak, so it cycles around.

GH: Or even that the title implies a sort of manic-depressive—

VG: Right, if you were irrationally exuberant, you’re easily disappointed.

GH: I don’t know how many of you saw the Urs Fischer show at the New Museum. Those mirror boxes were so fascinating because they implicated the viewers. We were inside of them as we passed by. Seeing ourselves behind these objects that were very funereal yet glamorous. I found that work successful, and related in a lot of ways. Even though they cost a lot of money, the objects depicted were cheap.

GWS: I don’t have a background in positive psychology; I have a much more solid background in Jungian, process-oriented psychology, like what Jackson Pollock underwent—psychoanalysis. That aspect of the history of psychology and art is more ripe and interesting for me. It’s less ethically loaded and more about happiness.

CWY: Jungian psychology is more about happiness than positive psychology?

GWS: Process-oriented? Yeah, I think so. There are many aspects of experience and the flow[2] of experience, and also, the meaning of objects that one takes in your life.

PM: I think what you’re suggesting, in part, is the potential for manipulation.

JDP: I thought Kant was saying that the experience of beauty is about a cognitive reckoning of that subject. It would be hard to say we could experience something without thinking through it. My suspicion or skepticism about cults is the way they shut down your thinking. They insist on a direct engagement over criticality. Positive psychology is often associated with that, like est, which became Landmark Forum. Its roots in the human potential movement here in the Bay Area is pretty interesting stuff, especially considering that people like Yoko Ono and Bruce Conner did est. So, I want to resist this impulse to have it be just an experiential thing—maybe it’s just the skepticism I bring to art.

Audience member: The work seems to reflect a desperate optimism…. Desperately trying to make a happy, safe cocoon….

Steven Barich: One thing that I like about this show is that I feel like I’m left on a fence. Whether I go the route of the added value of craft—obviously there’s a lot of the artist’s sincerity in making these pieces—but on the other side is the critique of the show, of whether I should like it or not like it, because of what I know about the cross-cultural value-added. So I have to walk in here and make this choice. That’s why I think it’s interesting to talk about it as an experience—because, as said before, it becomes a reflection. What you bring is the added value. I think you could walk away being quite dismissive of the object and just talk about the meaning of the show, or you could see the artist’s hand and talk about that just as you would talk in a knitting circle….

1. Alfredo Jaar and Adriana Valdes, Studies on Happiness: 1979–1981, Barcelona: Actar [1991] is available on Amazon.

2. ‘Flow’ as a positive psychology concept is credited to Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, author of Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, New York: Harper and Row [1990], also available on Amazon.